Lunt, P., and X. Luan, 2022, SE Asian Cenozoic larger foraminifera: taxonomic questions, apparent radiation and abrupt extinctions: Journal of Earth Science

This was a detailed review of an important fossil group, which was used to date South East Asian sediments for fifty years before the arrival of planktonic biostratigraphy, and the larger foraminifera are still important in dating shallow marine carbonates.

The larger foraminifera are an unusual and mis-understood fossil group. This paper was allowed to go over the normal length limit in this journal as it brought together a lot of data on three topics. I think it is a useful paper that shakes-up carbonate micropalaeontology, ties together the disjointed local studies, provides a testable evolutionary framework, and makes the subject interesting again

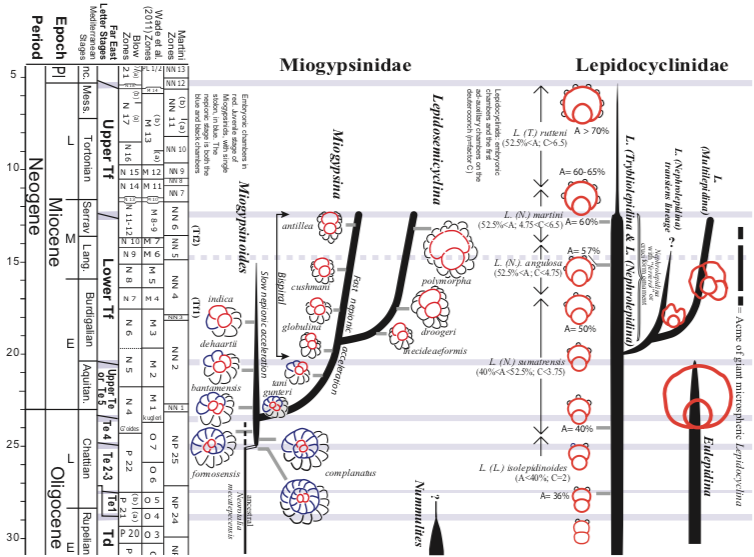

First: “what is a species of larger foraminifera?” This is an example of framing bias; with many modern workers approaching the problem of taxonomy with an existing perspective of “what species should be”, guided by ideas based on metazoan palaeontology. It is necessary to stand back and ask what is an appropriate scale of observation? How do we distinguish evolutionary morphologies from ecophenotypic forms? The answer is not easy as the group is characterised by evolution through anagensis – the evolution of morphology in a gradual fashion, as opposed to cladogensis that assumes branching off of distinct forms. Anagenesis is not handled well by the Linnaean naming system and the rules of the international code for zoological nomenclature (ICZN) that assumes distinct morphological “branches”. There has been a problem with workers naming new species on the smallest difference and overlooking the gradual anagenic trend. Seeing this anagenic trend requires good age control, something many prior workers lacked. Even the best papers had only marginal data on maybe just one type of other stratigraphic data, and often very incomplete data (sometimes just reporting a zonal assignment without background on actual fossil content, in shallow marine settings with depleted planktonic faunas). When this age data is examined then it appears that the major lineages of Oligo-Miocene larger foraminifera share the same anagenic trendsfrom the west Mediterranean to Papua; suggesting that each genus was a single, widespread genetic lineage evolving slowly. Some workers had reported slow migration of some forms across the Mediterranean to Indo-Pacific ocean, which would raise the topic of allopatric (geographic) isolation and separate areas of evolution, but this is easily disproved with good planktonic biostratigraphy supported by Sr dating.

Secondly, the data on the Letter Stage boundaries is reviewed, again calibrated to planktonic and isotopic age control. There are many accounts and figures of the Letter Stages in reports by European workers, with little direct experience of South East Asian data (where the Letter Stages were defined), which have varying and often quite inaccurate representation of where the Letter Stages boundaries are on modern time scales.

Thirdly the dates on the major extinction events and the style of evolutionary radiation between them is examined in light of the simplified view of taxonomy. A high number of species − or even genera − does not mean high diversity, but is mostly an artifact of taxonomic style of prior workers. An attempt is made to link the natural pattern of diversity through time with external causes, and while there appears to be a strong correlation of extinction to major unconformities in South East Asia, this is flagged as potential coincidence. For example, mass extinctions such as on the Eocene-Oligocene boundary are probably linked to global changes, not just the widespread subsidence and unconformity across eastern Sundaland that appears to have been at exactly the same time.

The paper has been accepted. Contact me if you want a pre-print. When published it will be open source, and I will replace this sentence with a link.

Be First to Comment