William Shakespeare suggested that names are not important: “A rose by by other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet), but names are only unimportant when they are used consistently. Apply the same name to different things and you have a problem. Stratigraphy is a jargon-rich science and, knowing that, one would think we would be careful with our names, but we are not. There are many examples of this, but in this post I want to talk about the so called “Cycles” of Sarawak.

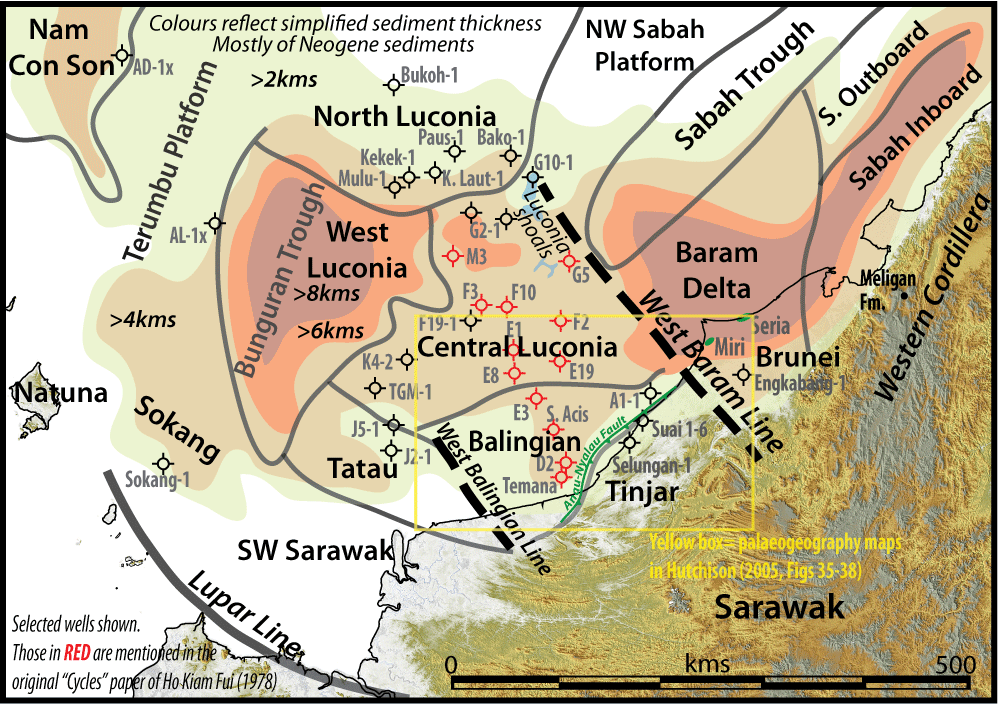

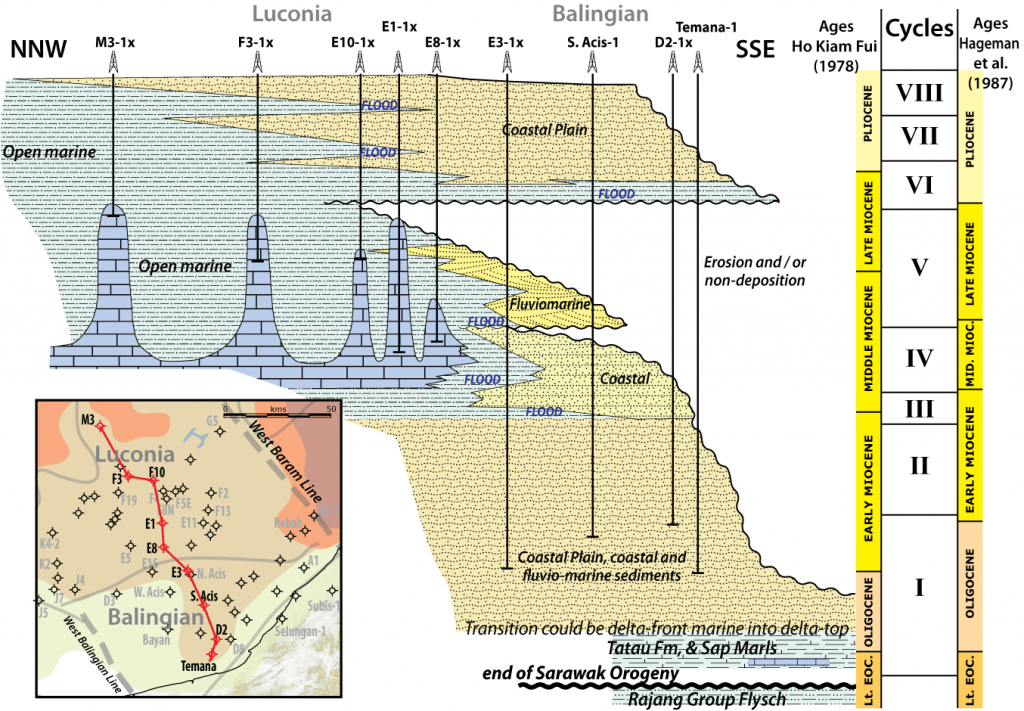

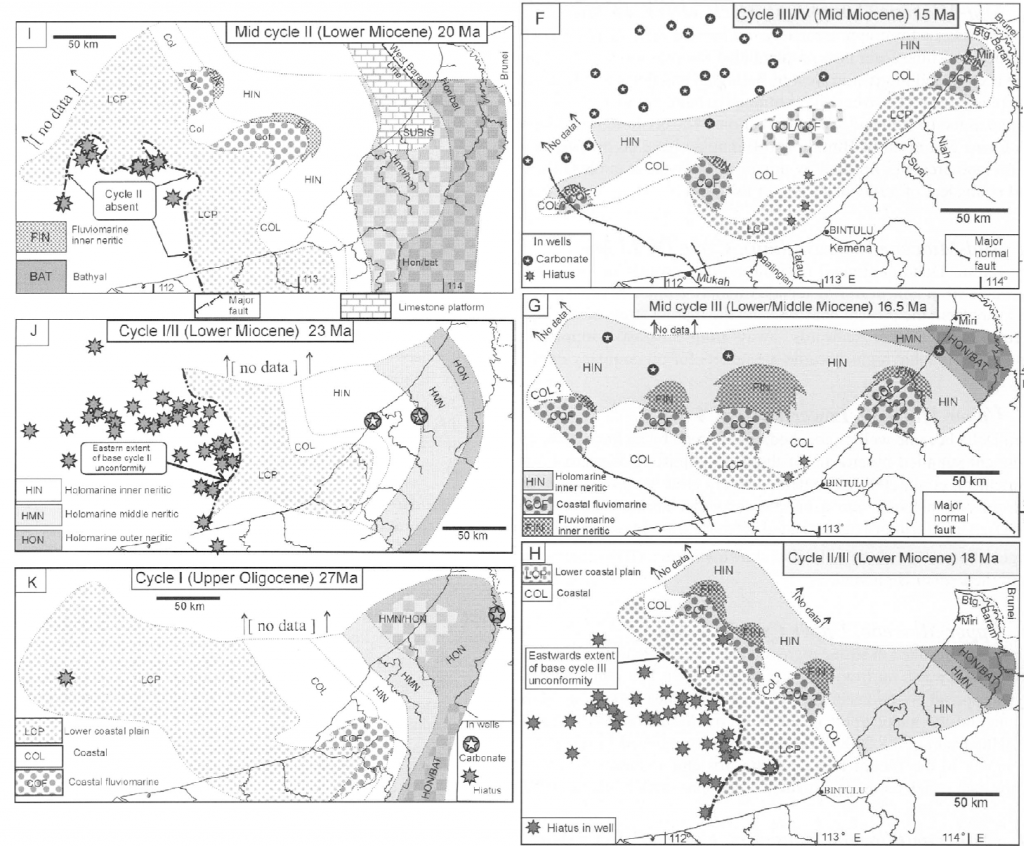

As I noted in a 2017 review, these units were expected to be repeated cycles of transgressive-regressive deltaic sediments, based on Shell’s experience of what worked locally in the Miri oil field, but expanded to a larger, regional scale. As exploration of the extensive offshore Sarawak area proceeded, the expected variation was found, but soon realised to have a tectonic overprint (see maps in Hutchison, 2005, Figures 35-38, shown in part below). The direction of sedimentation rapidly rotated through 90 degrees as the basin changed, then the Bunguran Trough in the west rifted open (partly over an area that used to be a high and a sediment source), then major uplift in the SE (elevation of the present onshore area, bounded by the Anau-Nyalau Fault). However the passive name “Cycles” stuck, for eight units from Cycle I to VIII (the oldest being I).

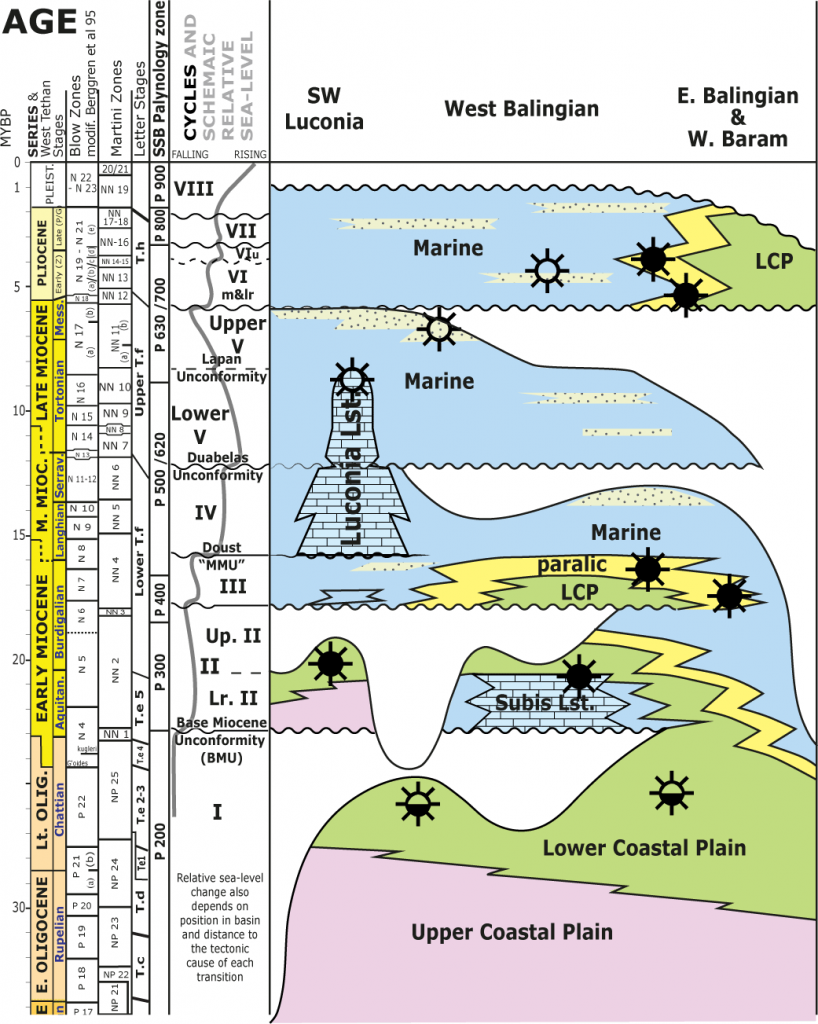

This very practical, natural, scheme was great, but it was poorly documented – at least outside Shell – while the world of Cenozoic stratigraphy was being revolutionised by modern time scales from planktonic biostratigraphy calibrated to ocean drilling (ODP) time scales (1970s to mid 1980s). In the mid 1990s a PhD student, Ismail Mat-Zin, read the available Shell reports, and he concluded that the Cycles might be Haq et al. (1987) 3rd order sequences, based on the published, idealised, description of what a Cycle was supposed to be. However, on Petronas’s regional seismic data he saw that tectonic events dominated the development of the basin, and tectonic unconformities separated the natural “megasequences” of sedimentation, which he named T1S to T7S. Ismail Mat-Zin had taken the published Shell stratigraphic summary, based on pre ODP time scales (Ho Kiam Fui, 1978), and compared this to the modern data. He saw a vague correlation of the Cycles to some of Haq’s eustatic events (not hard; there are enough of them), but more importantly he saw no correlation between the published Cycle boundaries and the boundaries of his tectono-stratigraphic megasequences, dated to modern time scales. However if one corrects the underlying 1970s Shell biostratigraphy on the Cycle boundaries to the ODP based time scales there is a perfect match. By being starved of the basic data, what Mat-Zin had done was effectively re-prove the Cycles concept. Only the Cycle III to IV boundary was overlooked as this extensional paraconformity was not well captured on the particular grid of seismic data made available to Mat-Zin for his studies.

This is a very similar issue to the 1964 “Lower Miocene” age given to the Kudat Formation in NW Sabah (actually containing Letter Stage Te2-4 microfossils, translated to Lower Miocene using old time scales) that survived as “Early Miocene” into modern papers up to at least 2013, even though since 1984 we have known Te4= end Oligocene and Te5= base Miocene. Similarly, the old mis-dating of the Cycles lived on.

Many industry workers had copies of an unpublished report by Hageman et al. (1987) who updated the older Shell work to the new ODP times scale, although it was not available to PhD students like Mat-Zin. Alternatively, reading Shell well reports or studies reveals the biostratigraphic sources dating the original Cycles. This was “cryptic data”; hidden from most workers. So as a result the Cycle III, which lasted up until just before the Orbulina datum and was, by modern definition, Early Miocene, but was wrongly placed in the early Middle Miocene by some. This issue altered nearly all the Cycle boundaries. The Cycle I-II boundary that virtually coincided with the Oligo-Miocene boundary in the main study area in the west Balingian and Tatau Provinces (effectively its type location) was shifted when explorers began drilling in distant North Luconia, so that a large part of the Cycle I was extended a long way into the Early Miocene. (The boundary not drilled in between due to the thickness of post Cycle III sediments). The angular Oligo-Miocene unconformity, so clear on seismic, and which separated Cycle I coastal plain from Cycle II coastal plain to paralic facies in the type area could no longer be correlated the massive unconformity between Oligocene delta plain sediments and earliest Miocene bathyal clays in North Luconia, as this was now an “intra Cycle I unconformity” in the newly corrupted scheme.

This is why Mazlan Madon and I (and other specialist at Petronas) thought it important to review this history in our 2017 paper. Thanks to the Geological Society of Malaysia, open source, no paywall (link here). Unfortunately we still have a tower of Babel, with a confusion of workers speaking different jargon when discussing the fundamental, natural, sedimentary units of the entire western South China Sea. Confusion persists even in new publications. What should be Cycle IV is called Cycle III etc., and this does matter. It greatly devalues these important natural stratigraphic units through confusion. It makes them seem “old-fashioned” and irrelevant. But, as Mat-Zin proved through independent testing, they are very real, and they cannot be ignored.

Beyond embarrassing confusion, the science also suffers. The Cycles are tectono-stratigraphic units with boundaries that increase in magnitude of effect close to the tectonic cause, and fade to insignificance with increasing distance. This is a distinguishing property from the eustatic sequence boundaries, which are abrupt changes in sediment accommodation space of the same magnitude around the world. Therefore the Cycle II to III boundary fades west to east across offshore Sarawak, and near Brunei they combine into a unit that is called Stage III in southwest Sabah. Mapping out the properties and extent of these tectono-stratigraphic boundaries is a fundamental description of a dynamic geological system. Their nature also means they cannot be directly correlated with eustatic changes. In other words, if you find an unconformity in your well and on your seismic, and it can be dated to correlated with a tectono-stratigraphic boundary, and the magnitude of facies contrast across this unconformity fits the mapped trend of the tectono-stratigraphic event, then it is a part of that process. If you identify a sea-level profile (curve) that has the same pattern in time and magnitude of change in basins globally, it is eustatic and therefore contains no information about the tectonic development of individual basins or the large scale sedimentary sequences that were controlled by them.

As pointed out by Miall (1992) it is doubtful if the high frequency eustatic sea-level changes postulated can be reliably identified and distinguished. Some specialists in SE Asia claim they can recognise a high frequency signature and use it for correlation. That’s great, but recognise it for what it is, and the limitations of its associated stratigraphic properties. What we have done in the meantime is make a mess of, and neglected, the more important “play-scale” tectono-stratigraphic framework by shoddy treatment of names and conventions. We have not used this valuable tool to describe the dynamic evolution of even the relatively stable Sundaland core of SE Asian geology. We cannot say to our funders that we understand either the geology or petroleum potential of the region, because we cannot explain basics such as why the Luconia Limestone occurs in Central Luconia and on the Terumbu Platform, symmetrically across the limestone-free Bunguran Trough, but nowhere else in SE Asia with the same initiating, modifying and terminating ages. We got lost because we didn’t understand how to distinguish things with reliable names.

References

Hageman, H., P. Lesslar, and Wong Chen Fon., 1987. Revised biostratigraphy of Oligocene to Recent deposits of Sarawak and Sabah. Unpublished; Sarawak Shell Berhad.

Haq, B. U., P. R. Hardenbol, and P. R. Vail., 1987, Chronology of fluctuating sea levels since the Triassic. Science 235, 1156-1167.

Haq, B. U., J. Hardenbol, and P. R. Vail., 1988, Mesozoic and Cenozoic chronostratigraphy and eustatic cycles. Sea-level changes; An integrated approach SEPM Special Publication 42, 71-108.

Ho Kiam Fui., 1978, Stratigraphic framework for oil exploration in Sarawak. Geological Society Malaysia Bulletin 10, 1-13.

Ismail, Che Mat-Zin. 1996. Tertiary tectonics and sedimentation history of the Sarawak basin, east Malaysia. Durham. PhD Thesis. Available online.

Ismail, Che Mat-Zin, and M. E. Tucker., 1999, An alternative stratigraphic scheme for the Sarawak Basin. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 17, 215-232.

Lunt, P., and M. B. H. Madon., 2017, A review of the Sarawak Cycles: History and modern application. Geological Society Malaysia Bulletin 63, 77-101.

Madon, M.B.H. 1999. Geological setting of Sarawak. In The Petroleum Geology and Resources of Malaysia, ed. L.K. Meng, 273-290. Kuala Lumpur: Petronas.

Miall, A. D., 1992, Exxon global cycle chart: An event for every occasion. Geology 20, 787-790.

Be First to Comment