“The Crocker Formation, which forms the entire coastal zone and foothills of Western Sabah, is considered by many workers as a part of an uplifted Upper Cretaceous to Lower Miocene accretionary prism that resulted from the subduction of a proto-South China Sea oceanic crust underneath Sabah (Tan & Lamy, 1990; Hazebroek & Tan, 1993)”

(introduction to a paper published in the past 2 years)

“The proto-South China Sea, was subducted beneath the Sunda Shelf, during the Late Cretaceous times. The cessation of subduction occurred in the Miocene, when large blocks of continental shelf blocked the Subduction trench, causing collision between the leading edge of the South China Sea continental realm with the Crocker-Rajang accretionary margin of Northwest Borneo.“

Introduction to a 2021 online talk on North Borneo sedimentology

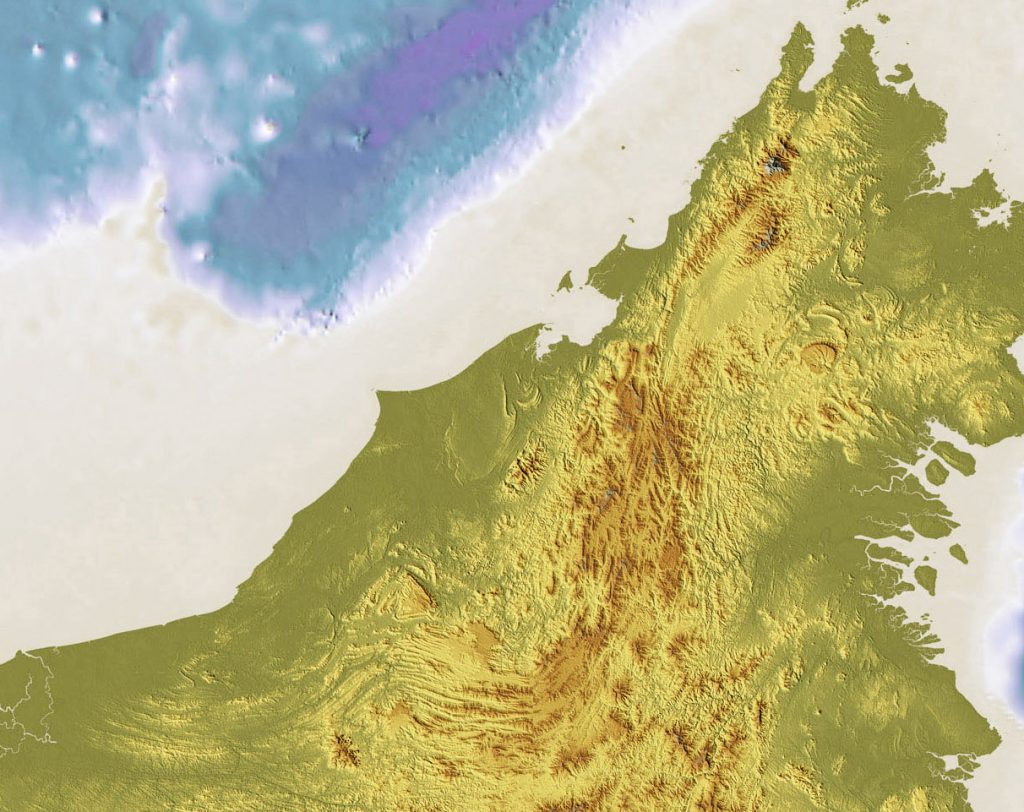

This is a recurring pitfall for students, and it neatly illustrates the importance of time in constructing geological frameworks. If you examined a high resolution topographic image of Borneo (e.g. SRTM below) you will see a compressional lineament in the west deforming the Rajang Group with east-west striking lineaments, but then these lineaments trends roughly northeast and then north.

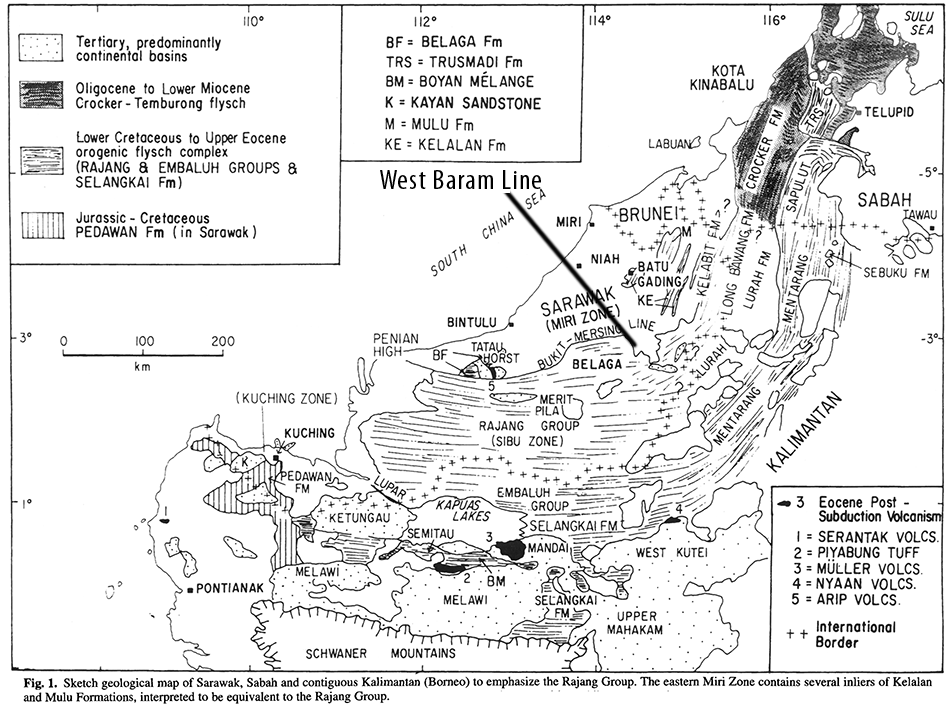

The compressional lineaments are bent several times as shown in the map below from Hutchison (1996), until by Sabah and the northern tip of Borneo in the Kudat Peninsula the trend is about 110˚ (WNW to ESE).

The facies being deformed is invariably deep marine flysch. As the recent quote at the top of this page shows, it has become a dogma to consider these deep marine units, lumped under poorly defined terms such as the “Crocker Formation” as a trench-fill deposits, tens of km thick. These deep marine deposits were compressed to form an “orocline” (Hutchison 2010).

As both Hutchison (1996) and Hall and Breitfeld (2017) point out, there is a fundamental division of this oroclinal deformation. To the south the deformation of the Cretaceous to mid Eocene Rajang and Embaluh (in Indonesia) Groups was active until about 40 or 38 Ma (approximately the Middle to Late Eocene boundary). This Eocene deformation has long been termed the Sarawak Orogeny and the termination of this deformation produced the Rajang Unconformity (Liechti, 1960). The field reports in the north, such as Collenette (1965), show that this deformation faded rapid north-eastwards, and there it is just a low angle bedding relationship seen on photogeology between Eocene and Oligocene formations in central Sabah.

To the north the deformation was named by Hutchison (1996) as: “Mid to Late Miocene inversion of the West Crocker-Temburong basin to form the Crocker Ranges of Sabah has never been given a name, but the term Sabah Orogeny seems appropriate. Its cause remains obscure.”

Hall and Breitfeld (2017) emphasised this division and simplified it, saying the main boundary was at the West Baram Line. They argue that there were undoubtedly two orogenic events, with different geography and timing, with the second event grading into the prolonged Sabah Orogeny.

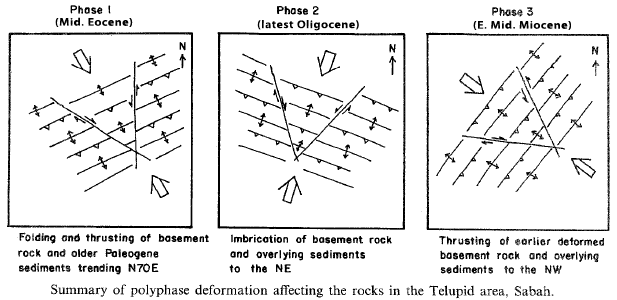

But even this is over-simplified. There are three events, once all age data is included. Without this knowledge one cannot propose tectonic or regional geological models that make sense. There are three distinct geological movement and three terminations, and each movement has its own geography and distribution of effect. The structural geologist Felix Tongkul, studying the deformation history of the Telipid area of Sabah saw these three phases:

We have known since Reinhard and Wenk (1951, p.21 – with their emphasis) “This maximum [tectonic] movement took place between Te4 and Te5. This is the most important Tertiary orogeny of North Borneo”, a view repeated by Liechti (1960). Then Brondijk (1962) formalised this unconformity, which would become known as the Base Miocene Unconformity (the age of the Te4-5 Letter Stage boundary) as the top of the Temburong Fm. (part of the Crocker Formation or Group) and the younger Setap Shale.

A blog is not the best place to slog through all the details, but put simply; the Sarawak Orogeny was compression of a Mesozoic remnant oceanic basin during the early Cenozoic, which was strongly focused in west Sarawak and terminated at the Rajang Unconformity within the Eocene at about 40 to 38 Ma. Then there was around ten million years of negligible compression until Letter Stages Te2-4 (Late Oligocene) compression of northwestern Sabah, that produced an inverted L-shaped lineation including the 110˚- striking deformation of the Kudat Peninsula (Lunt, in press). This affected most of northwestern Borneo and terminated at the Base Miocene Unconformity, which is overlain by Te5 limestone in several places (South Banggi, Gomantong Fms.). Then there was a seven million year pause in tectonism followed by the onset of the Sabah Orogeny in latest Early Miocene times, which affected northwestern Borneo and the island of Palawan until mid-Pliocene times (Lunt and Madon 2017).

By recognising time as a crucial geological property, and not one that requires a Proto-South China Sea or its subduction under Sabah (or an accretionary wedge). Yet the literature is still full of mis-direction and, in the current jargon, “fake-news”. Note that none of the three deformations summarised above include sheared mélanges, which are diagnostic of accretionary wedges. These are only found south of the Lupar Line (south of the area marked as “Sibu Zone” on the sketch map above). These were produced by genuine accretionary processes during Mesozoic subduction that gave rise to the granites of the Schwaner Mountains.

Stratigraphic consultants have all but disappeared. There seem to be few able to read and explain the solid and reliable work from past generations. Specialists, especially structural geologists have been let down. This is what is holding geology back in SE Asia. We are well and truly stuck in a rut.

References

Brondijk, J.F., 1962. A reclassification of a part of the Setap Shale Formation as the Temburong Formation. British Borneo Geol. Survey Ann. Rept., 56-60

Collenette, P., 1965. The Geology and Mineral Resources of the Pensiangan and Upper Kinabatangan Area, Sabah (12). Malaysia Geological Survey Borneo Region.

Hall, R., Breitfeld, T.H., 2017. Nature and demise of the Proto-South China Sea. Geological Society Malaysia Bulletin 63, 61-76

Hazebroek, H.P., Tan, D.N.K., 1993. Tertiary tectonic evolution of the NW Sabah continental margin. Special Publication Geological Society Malaysia 33), 195-210

Hutchison, C.S., 1996. The Rajang accretionary prism and Lupar Line problem of Borneo. Special Publication Geological Society of London 106, 247-261

Hutchison, C.S., 2010. Oroclines and paleomagnetism in Borneo and South-East Asia. Tectonophysics 496, 53-67

Liechti, P., 1960. The geology of Sarawak, Brunei and the western part of North Borneo (Bulletin 3). Kuching Sarawak: Geological Survey Department British Territories in Borneo.

Lunt, P., in press. Re-examination of the Base Miocene Unconformity in West Sabah and its part in the tectono-stratigraphic development of the region. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences

Lunt, P., Madon, M.B.H., 2017. Onshore to offshore correlation of northern Borneo; a regional perspective. Geological Society Malaysia Bulletin 64, 101-122

Reinhard, M., Wenk, E., 1951. Geology of the colony of North Borneo. Geological Survey Department of the British Territories in Borneo (Bulletin) 1, 160pp

Tan, D.N.K., Lamy, J.M., 1990. Tectonic evolution of the NW Sabah continental margin since the late Eocene. Geological Society Malaysia Bulletin 27, 241-260

Tongkul, F., 1997. Polyphase deformation in the Telupid area, Sabah, Malaysia. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 15, 175-183

Be First to Comment